The three inputs you need to nail your narrative

Great narratives aren’t built in a vacuum. Your positioning and messaging is always relative. What do I mean by that? Well, the market’s always shifting, the competitor landscape always evolving, and so a narrative that makes sense today might make little sense tomorrow.

Now, that’s not to say you should be chopping and changing your narrative every few weeks. That’s overkill. Plus it takes a good few months for your narrative to really bed in. So you’d be essentially building from scratch every time. No thanks.

But there is a useful lesson to be learned here, and it’s this:

You have to be fully aware of the space around you.

I realise that makes me sound a little like a jedi master, but it’s true. If you don’t know enough about the world your product lives in, then your narrative, positioning, messaging, it’s all just a stab in the dark.

And unless you have the force, that’s not gonna end too well.

At the start of every project, no matter the size or scale, I always check three things. Sometimes the info’s given to me and I just need to learn it. Sometimes I have to go out and find stuff out for myself. But for me it’s a non-negotiable. If I don’t have the opportunity to do this prep work then the project will be shit. End of.

So, what are these mysterious three things I speak of?

They are, in no particular order:

Speak to Stakeholders

Powwow with Prospects

Check out Competitors

If you can truly understand those three things, then the path to your narrative will look pretty darn clear.

And today I’m going to walk you through each in turn, explaining why it’s valuable, how to gather the data, and most importantly how to use it.

Let's go.

Speak to Stakeholders

First, let’s define what I mean by stakeholders. For me, your stakeholders are the key people that this work will impact.

Now, this can be a little tricky to determine, as it can vary depending on the org structure at your startup. Plus, your narrative should really be impacting everyone if rolled out correctly. But that’s a different story.

Anyway, here’s a list of people you should probably chat to:

Founders — Goes without saying. It’s their company. Their baby. And they have the most useful insights about where your product sits in the market.

Marketing — These are most directly impacted by this work. The narrative is their responsibility in the first place. Rolling it out will be their job.

Sales — Again these are strongly impacted by the work. And they have some great insights on your prospects (another of the three data sources).

Of course, your startup might have roles around Growth or RevOps or whatever the latest buzzword for marketing is. So you might need to read between the lines here a little.

Why is this valuable?

Each of those three “departments” has some extremely useful insights when it comes to building your narrative.

Founders obviously started the company in the first place. They came up with the product. Which means they’re better-placed than anyone to explain why they did that in the first place. They should know the landscape as well as they know their local neighbourhood.

Marketing is fully embedded in the market. Or at least you’d hope so. Which means they have a keen understanding of competitors and customers. They know what works from a demand gen perspective. And they have a non-biased view, unlike some founders. Not naming names…

Sales are on the frontlines. They talk to prospects every day. They know why you win deals. They know why you lose deals. And so they’re insanely valuable. Not to mention that they’ll also be using the narrative in sales calls, so they need to be onboard from the start.

So speaking to stakeholders is crucial for getting those early insights. It also helps to align people around your narrative project in the first place. This early buy-in makes your life so much easier later on in the process.

How do you get the info?

I find the most effective way to do this is to treat it as an interview with the relevant people. One on one is best. A conversation is much more free-flowing and gets to more interesting nuggets. You’re able to push deeper into their thinking if it sounds like a useful avenue.

This is opposed to questionnaires or surveys which, while useful, often miss the nuance.

If you’re uncomfortable with that kind of unstructured interview, make a list of questions in advance. That’s totally fine too. Send them over beforehand so they can think and prep.

Some of the things you want their opinion on:

Why does our product exist?

Who gets the most value from it?

What problems does our product solve?

Why do those problems need solving?

How does our product solve them?

What’s the unique value?

How do you use the info?

Firstly, remember that this is an exercise in gauging opinion. None of this is entirely factual. This isn’t the decision-making part of the process. People will likely disagree in places. That’s normal. That’s expected. That’s why you’re doing all this in the first place.

So you have to take what you learn here with a pinch of salt.

But you should be looking out for two things: commonalities and conflicts.

Commonalities are interesting because if everyone agrees on something, it’s more likely to be valid. This will show you where your current positioning and messaging is stronger.

Conflicts are interesting because it suggests a gap in your positioning and messaging. If people can’t agree on something internally, then imagine what external people (prospects and customers) must be thinking. The conflicts need to be cleared up as part of your narrative-building.

Finally, these are useful insights to apply to the other two areas I’m talking about today. See them as potential lenses to see prospect and competitor data through.

Powwow with Prospects

A lot of advice around positioning and messaging says you should talk to customers. I think that’s slightly misleading. Why? For one simple reason: it isn’t aimed at your customers.

Nobody is marketing to their customers. Nobody is selling to their customers. At least not in the sense we’re talking about.

You’re marketing and selling to prospects. To people who haven’t yet bought your product. And so your narrative, your positioning, your messaging - it all needs to appeal to them.

It’s a subtle mindset shift, but a really important one to make.

Why is this valuable?

As I just mentioned, your prospects are ultimately who you’re doing all this to attract in the first place. If you want to be your prospects’ only possible option, then you need to figure out what they need.

Sounds simple in theory, but this can actually be pretty difficult. But without listening to what your prospects have to say, it’s virtually impossible.

So by chatting with prospects and digging deep into their aims, their needs, and their problems you’re giving yourself a much better chance at building a narrative that resonates with them. After all, the aim is to make your prospect the hero of your story. If they don’t see themselves in that hero, then the rest of the narrative falls flat.

How do you get the info?

This bit is where I see a lot of startups go wrong. They think all they have to do is speak to prospects and ask what they need. Then go away and build that thing. Easy.

Except it’s not that easy.

By now everyone knows that famous Henry Ford quote: "If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”

But people misinterpret it to mean they should never talk to their prospects.

I interpret it a little differently.

You see, if Ford had spoken to prospects and asked what they wanted, they probably would have said faster horses. They would’ve come up with a solution.

But the solution isn’t what you want from prospects. You want the problems they’re facing. Get the problem from the prospect, and then go away and devise your solution. In Ford’s case, he would’ve discovered that prospects wanted to travel faster. His solution to that problem? The car.

I use a tried-and-tested chain of questions to get to that point. I’ll share them with you now. (Of course I’m not suggesting you just robotically move through each in turn. It should be a free-flowing conversation. But these will help steer you in the right direction.)

What are you currently trying to achieve? (In the context of your product’s category - eg. if you’re selling a CRM, then it’s going to be sales related.)

How are you currently trying to achieve it?

What works well about that solution?

Where does that solution fall short?

What’s the biggest problem you’re struggling to solve?

Notice how those question don’t ask them to create a solution. They ask what they’re currently doing (the Status Quo part of the narrative) and where it falls short (The Big Bad part of the narrative).

If you can get this info from a handful of your ideal prospects then you’re in a really strong place when it comes to thinking about your narrative foundations.

How do you use the info?

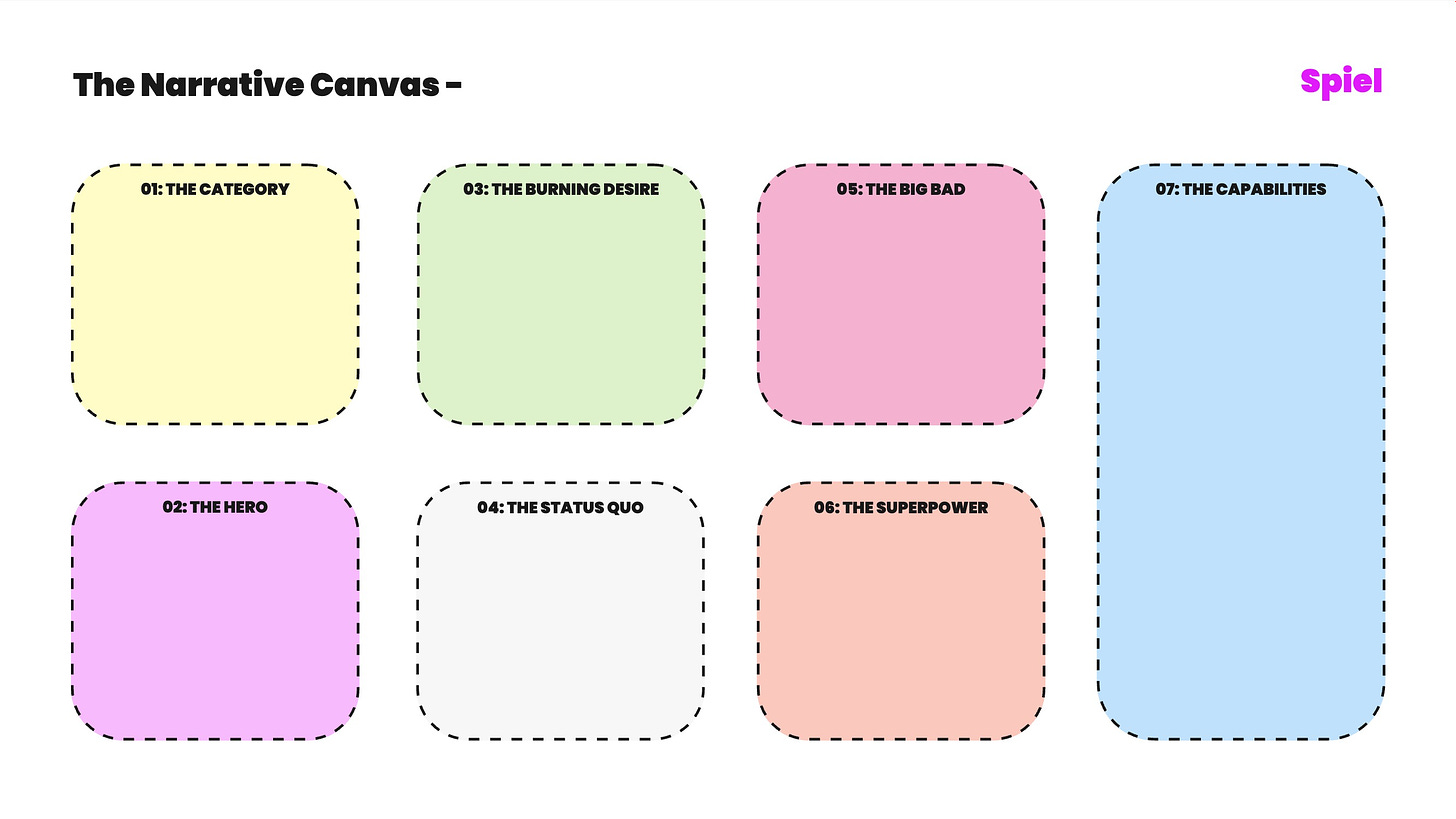

Like I just alluded to, some of the answers you get here map directly onto my Narrative Framework, pictured below:

You’ll now have a pretty good idea of what they’re trying to achieve, how they’re trying to achieve it, and the problem with that solution. That gives you The Burning Desire, The Status Quo, and The Big Bad respectively.

Of course, sometimes it won’t map perfectly onto the framework. You’ll still need to do some thinking and deciding. Especially if prospects are saying slightly different things to one another.

But ultimately this gives you important insights into where your prospects are on their journey.

You can also use this as a great source of language inspiration. Your messaging should align with how your prospects talk (to a certain point at least). You’ll have a better ear for that after talking with them.

Check out Competitors

For some reason, a lot of people in the B2B SaaS world think you should just completely ignore your competitors.

I call this Ostrich Syndrome. You bury your head in the sand and hope they go away.

Some people assume that looking at the competition dooms you to copy them. For me, it’s the opposite. Knowing what your customers are positioned around, seeing their messaging, and understanding their product gives you a wealth of information to actually prevent you from copying them.

So yeah, you need to be checking them out.

Why is this valuable?

Ultimately, whether you like it or not, you’re at war with your competitors. If your products are basically the same (at least in the eyes of prospects) then you’re directly competing for attention, for mindshare, and for budgets.

Now, would you go to war without trying to gather some intel on your opponents? Of course you wouldn’t. That would be ridiculous. I mean, it’s why James Bond exists.

The better you understand your competitors, the better you understand where your product sits in the market. Positioning is relative to those around you. Think of competitor analysis as your map to that space.

The ultimate aim of building your narrative is to differentiate you and push you away from these competitors. But you can only do that if you know what you’re pushing away from.

So stop being an ostrich.

How do you get the info?

The first thing you need to know is who your competitors actually are. Because sometimes you think you know but you’ve got it wrong. There are three sources of info for this:

Your sales team — they should have an idea after talking to prospects

Your prospects — if you’ve done the previous section then you’ll have an idea

Comparison sites — Eg. G2, Capterra, etc.

Once you know your main competitors, the ones you’re losing customers to most often, then you can start to do some snooping.

Head to their sites and analyse what they’re trying to communicate. Some questions to consider are:

What problem are they focusing on? (If any…)

What’s their core feature / functionality?

How do they frame their solution?

What kind of language do they use?

Do they have a differentiator?

The more info you can gather here the more you have to use.

How do you use the info?

Once you’ve gathered all your competitor data, there are several different ways you can use it. The main ones are:

Identifying category norms

Finding space

Validating narrative ideas

I’ll explain each of these in turn…

Category norms:

Category norms are essentially things that are taken for granted in your industry. They’re table stakes claims. In the CRM category, for example, being able to set follow-up reminders is now par for the course. Every CRM now offers this. It’s core functionality that’s expected by a product in this space.

When you look across multiple competitors, you get a better sense of what all of them have in common. These product features, use cases, and capabilities are your category norms. There’s nothing wrong with communicating these, but you won’t be differentiating yourself with them.

Finding space:

This is the whole point of this exercise, and competitor analysis gives you a good idea of potential spaces to move into. This can be tricky, as what you’re actually doing here is looking for what isn’t there.

Ask yourself what competitors are NOT talking about, and then ask why. If it’s simply because it’s a weakness of theirs, then that could be a potential gap in the market for you to inhabit.

Validating narrative ideas:

It’s natural at this info-gathering stage to have some early hypotheses about what your narrative could focus on. Even more so if you’ve already spoken to stakeholders and prospects.

If that’s the case, then competitors analysis gives you a good way of at least slightly validating those ideas. If your cool narrative idea is already taken by one or two competitors, then it might be worth steering away from it and letting it go.

But if nobody is talking about the focus of your narrative, or even better are saying the opposite, then you might be in a good position.

Let’s wrap it all up

Phew. That was a lot.

If all this sounds like hard work, that’s because it is. I wouldn’t have a job otherwise.

But my intention here isn’t to overwhelm you so here’s the one key takeaway:

The more information you can arm yourself with, the easier the actual narrative-building part of the process is.

So when you feel fed up of all this chatting and analysing and thinking, remember that future you will be thankful.

Or failing that, just get me to do it all for you.

Thanks for reading!