It’s 1943. The world’s at war. And the US military has a pretty big problem on its hands.

Their bombers are slowly but surely being wiped out by the German anti-aircraft guns. And those bombers cost an absolute fortune to build. Losing more isn’t really an option.

So they put together a research group, based out of the Statistical Research Group at Colombia University.

One of the members of this group was a mathematician named Abraham Wald. Growing up as a Jewish man in Austria, Wald knew first-hand how terrible the Nazi regime was, and counted himself lucky to have escaped. And now he had an opportunity to strengthen the US bombers and help them win the war.

Here was the issue:

It was clear that the planes needed more armour. But that armour was heavy. And the heavier the plane, the less manoeuvrable it was. The less manoeuvrable it was, the higher the risk of it getting shot down without being able to complete the mission.

So the question posed to Wald and the research group was this: “What’s the least amount of armour we need to protect the planes? And more importantly, where should it go?”

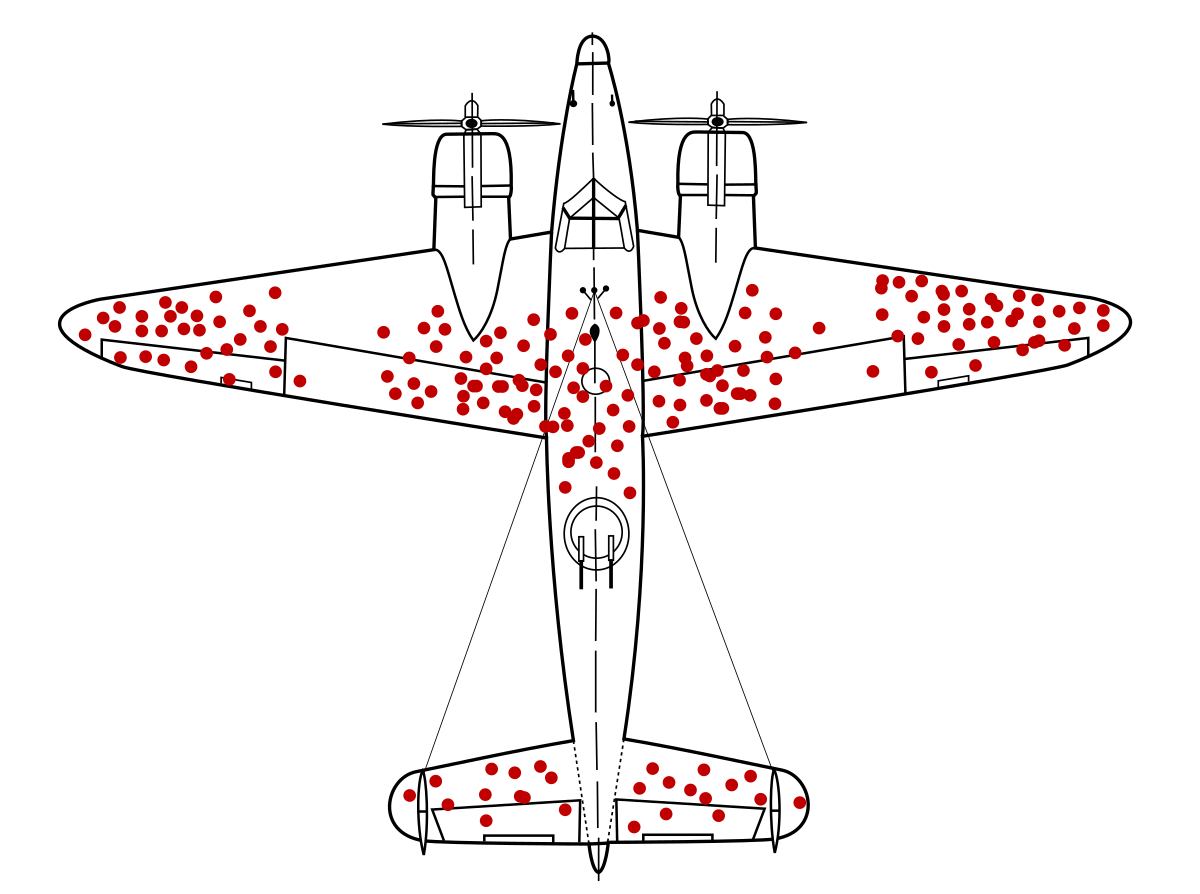

Wald was given some data. They’d mapped out the bullet holes on the surviving planes to see where most of the damage had been done.

It looked something like this:

Those red areas are where most of the bullets hit the planes.

The first conclusion that people jumped to was simply: Reinforce with armour the places marked in red. That’s where the damage tends to be done, so let’s give it some extra strength.

And on the surface that made complete sense.

Except, that is, to Wald.

Wald had a different perspective.

He declared that the armour should be placed on the parts of the planes that weren’t hit very often.

Why?

Because these planes returned home. Meaning the damage that was done to these planes didn’t take them out of the sky. Ultimately, it didn’t matter.

What this data was actually showing was the places a plane could be shot and survive.

And so, as far as Wald was concerned, it suggested that if planes were shot in the “clear” areas, that was where the damage was currently un-survivable. Planes that were shot there didn’t make it back home.

They reinforced the planes as per Wald’s suggestions, and the rest is history.

Wald’s ability to see what wasn’t there is often cited as an illustration of Survivorship Bias: our tendency to focus on things that survive a particular selection process and ignore the things that didn’t.

But I want to talk about the fact that Wald was able to look past the data and identify what it wasn’t telling us directly.

Because that’s the kind of thinking you need if you want to uncover the unique insights at the heart of your Radical Positioning strategy.

Let’s think about this in more relevant terms to founders and marketers who are trying to position their company.

One of the main inputs you’re likely to have when working on your strategy is customer research. Speaking to your customers about their problems can be a great source of insights. But only if you look for the radical ones.

What’s the difference?

Well, surface-level insights are pulled directly from the data you have.

Whereas radical insights are taken from what the data doesn’t immediately show you.

It’s probably best to give an example.

Imagine you’re trying to position a CRM. You talk to some customers and one of the most common things you hear is:

”I keep forgetting to follow up with leads.”

So you think to yourself, “Great, let’s build in some kind of reminder functionality.”

Except, this won’t differentiate your product in any way. Why? Because it’s a surface-level insight. If this many customers are telling you this, then they’re also telling your competitors this. And you’ll all build the same reminder functionality.

But if you think like Wald, and look a level deeper, you might stumble on something more interesting. A radical insight.

You might, for example, realise that these customers are all currently using CRMs. And these CRMs already have reminder functionality. And yet still people are forgetting to follow up.

You might then dig a little deeper and realise that the issue isn’t actually that people forget to follow up, it’s that they don’t think to use a CRM as a reminding tool.

And then you think of a solution. You decide to build a CRM that lives inside a customer’s calendar app. When they check their daily schedule, your CRM will be there to remind them of who they need to follow up with. They don’t need to even open their CRM to find out.

Suddenly you have something more interesting. You have something different. Something radical.

And it started by seeing what wasn’t there.

(NOTE: This is just an example that came to mind, I’m sure there are already solutions like this, but hopefully it helps to clarify what I’m talking about here.)

So next time you’re looking for strategic insights, take a leaf our of Abraham Wald’s book. Look deeper than those surface-level, obvious insights are telling you. And question whether the more interesting stuff is a level deeper. That’s how you find the kind of radical insights that lead to real differentiation.

Thanks for reading. As always, if you need to ask for any clarification on this don’t be scared to reach out and ask. Disagree with me? Let’s debate. It’s fun.

Yours radically,

Joe

PS. Not signed up to receive these emails yet? Now’s your chance.